Closing the First Nations employment gap will take 100 years

- Written by Reza M. Monem, Professor of Accounting, Griffith University

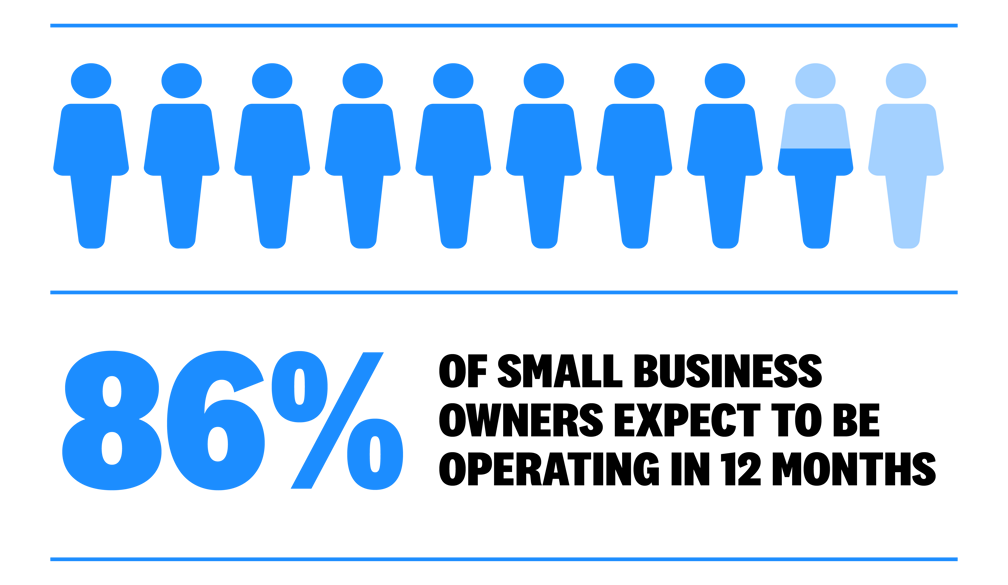

In 2008 Australia’s federal, state and territory governments set the goal of halving the employment gap[1] between First Nations Australians and others within a decade. That required, by 2018, lifting the employment rate for First Nations Australians from 48% to 60%[2], with the rate for other Australians being 72%[3].

So how are things going? Not well.

At the 2021 census the employment rate for First Nations Australians was 51%, while the rate for other Australians was 74%[4].

Assuming the employment rate for other Australians does not change, the rate of incremental gains in First Nations employment since 2008 suggests that closing the employment gap is going to take 100 years.

We have analysed the employment data published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics to get a more granular picture of why so little progress has been made.

Our results show the ongoing problems of low educational attainment and lack of employment opportunities in rural and remote areas, where the majority of First Nations Australians live.

What these statistics show

Before we continue, it’s important to note the following statistics use a slightly different way to measure employment (and unemployment) rates than that used in the Australian government’s Closing the Gap[5] reports, referenced above.

The Closing the Gap methodology measures employment as a percentage of all people aged 15 to 64. We’ve adopted the approach used by the Australian Bureau of Statistics for its unemployment data. This approach measures the employment rate as the percentage of people employed in the labour force – the labour force being anyone working or registered as looking for work.

The rationale for the Closing the Gap methodology is that the bureau’s measure overstates Indigenous employment, because First Nations Australians have a lower labour-force participation rate. That is, there is a greater proportion of Indigenous Australians that don’t have jobs but are not counted as unemployed because they aren’t registered as unemployed.

There are pros and cons to both approaches. We’re using Australian Bureau of Statistics data, so we’ve stuck with the bureau’s approach. It doesn’t substantially change the results, but it’s important to acknowledge the subtle distinction.

Educational attainment matters

Our first two graphs demonstrate the importance of educational outcomes.

Almost half of the First Nations Australians (49%) do not have a qualification beyond secondary education, compared with 31% of other Australians. About 12% of First Nations Australians attain university qualifications of a bachelor’s degree and above (graduate diploma or postgraduate), compared with about 37% of other Australians.

These differences in educational attainment are reflected in employment outcomes.

For the 6.7% of First Nations Australians who leave school before year 10, the unemployment rate is more than 25%. For those with no qualification beyond year 10 to 12 of secondary school, the rate is 16.7%.

Unemployment rates begin to equalise only with university qualifications. For every level of educational attainment less than a diploma, First Nations unemployment rate is at least double that of other Australians.

Location counts

There are likely multiple reasons for these stark differences in employment outcomes by education, including discrimination[8]. But one clear factor is geographic location.

First Nations Australians in remote and very remote locations are twice more likely to be unemployed than their peers in major cities (where the unemployment rate is still double that of other Australians). The more remote, the higher the rate of unemployment.

Why do the unemployment rates for other Australians show the opposite trend, with lower rates the more remote? Our best guess is this disparity reflects a combination of the effects of educational attainment, job opportunities available and labour mobility.

Non-Indigenous Australians in remote regions are more likely to have moved to these areas only after securing jobs upon attaining their schooling and qualifications in a big city. Governments often provide incentives[9] for those with the right skills to relocate to these regions[10].

This disparity presents a stark challenge for employment programs, given almost 60% of First Nations Australians live outside the major cities, compared with only a quarter of other Australians.

Commonwealth employment programs for remote regions have a vexed history, with the most recent program, known as the Community Development Program, being cancelled in 2021[13]. The Albanese government announced a replacement remote jobs program[14] in the May federal budget.

Read more: Albanese government announces $424 million to narrow a gap that is not closing fast enough[15]

Employment by occupation

The unemployment-related factors lead to differences in the occupational profile of First Nations Australians. They are more likely than other Australians to be employed in community and personal services or manual labour, and significantly less likely to be in a professional or managerial role.

Different approaches needed

These statistics show that, with the exception of those achieving postgraduate qualifications, First Nations Australians face multiple disadvantages in employment.

Read more: Why we aren't closing the gap: a failure to account for 'cultural counterfactuals'[16]

The lack of any significant progress in the past 25 years suggests just continuing with the same policies will achieve little.

Something has to change. Listening to those closest to the problem, and giving First Nations Australians a greater say in designing and implementing solutions would be a good start.

References

- ^ halving the employment gap (www.dss.gov.au)

- ^ 48% to 60% (www.dss.gov.au)

- ^ 72% (www.dss.gov.au)

- ^ 74% (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ Closing the Gap (ctgreport.niaa.gov.au)

- ^ Australian Government (www.closingthegap.gov.au)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ including discrimination (cdn.minderoo.org)

- ^ provide incentives (www.regionalwork.sa.gov.au)

- ^ relocate to these regions (www.nsw.gov.au)

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ being cancelled in 2021 (australiainstitute.org.au)

- ^ remote jobs program (www.indigenous.gov.au)

- ^ Albanese government announces $424 million to narrow a gap that is not closing fast enough (theconversation.com)

- ^ Why we aren't closing the gap: a failure to account for 'cultural counterfactuals' (theconversation.com)

Authors: Reza M. Monem, Professor of Accounting, Griffith University

Read more https://theconversation.com/closing-the-first-nations-employment-gap-will-take-100-years-205290