What makes a good tree? We used AI to ask birds

- Written by Stanislav Roudavski, Founder of Deep Design Lab and Senior Lecturer in Digital Architectural Design, The University of Melbourne

Grassy box gum woodlands once covered millions of square kilometres in southeastern Australia, but today less than 5% remains[1]. The loss of large old trees[2] has been a crisis for the many species of birds and other animals that depend on them for habitat.

Replacing this habitat is not easy. There is no quick way to create a centuries-old tree.

One thing we can do is make artificial structures that mimic the features of large old trees in degraded environments where trees cannot live or are too young and small. We have been working with the Australian Capital Territory Parks and Conservation Service to do just this in the Molonglo region of Canberra.

To build these artificial structures, we need to know what makes good habitat from an animal’s point of view. And to find that out, we developed ways to use AI and machine learning[3] to include non-human stakeholders[4] – in this case birds and trees – in the design process. In effect, we enrolled large old trees as lead designers, and birds as discerning assessors of their work.

Trees, birds and power poles

Molonglo hosts a once-thriving ecosystem that is now fragmented and damaged. Large old trees are increasingly rare.

These trees, some more than 500 years old, provide complex canopy structures that are essential for bird nesting, foraging and roosting. As urban development expands and old trees die, the challenge is to fill the gap left by these giants.

Modified utility poles and relocated dead trees (or snags) have previously been introduced into the region as substitute habitat. These structures can provide[5] important habitat features such as elevated perches, nesting boxes and bark that do not occur in planted tree saplings. However, it is very difficult to understand exactly which features of a large old tree are important to birds – which limits the value of artificial structures.

Carefully analysing imagery and other data can help us discern these features. For example, we and our collaborators found that birds prefer small horizontal branches[6] for perching and nesting.

From studying birds, we can learn their preferences for certain characteristics that have already been designed by trees. Our next challenge was to use this information to design better habitat structures.

Learning from trees

We used a process that involved data capture, predictive modelling and iterative design. AI and machine learning were indispensable in interpreting complex spatial data.

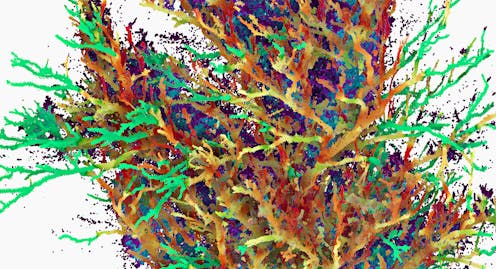

First, we mapped each tree by reflecting many millions of laser beams from each square centimetre of its surface to capture tree canopies as clouds of points. Then we used algorithms to identify and measure significant attributes such as orientation, size and linking of branches. A better understanding of bird preferences for these attributes can inform designs for artificial replacements.

Next, we developed statistical models to predict bird behaviour. These models were based on long-term observations of bird interactions[7] led by Philip Gibbons at the Australian National University. By simulating how birds might use artificial branches, we could refine our designs to better meet their needs.

Reimagining artificial habitats

To generate a variety of artificial tree crowns we developed further algorithms. Instead of judging the resulting designs by how much they resembled a tree to human eyes, we used our bird behaviour model to figure out how these structures might serve avian inhabitants.

Our additional goal was to create lightweight structures that are easy to install, reconfigure and remove. Our simulations showed that, compared to utility poles and snags, these structures can provide a significant increase in habitat suitability.

Returning to the field

We are currently building prototypes based on our designs, but the final step in this process will be field testing to find out what the birds think. Birds can provide feedback on the characteristics of artificial structures through their interactions with them. This testing will help make the designs even better.

Design processes, even for non-human stakeholders like birds and trees, are currently dominated by human perspectives and expertise. Our findings show how broadening the scope of creative contributions and judgements can improve the design process. The outcomes of this design process can take the form of “continuous services[8]”, sustainably providing shelter or other resources.

While we hope to build better artificial structures, it is important to remember that there is no true substitute for large old trees. We must also preserve the trees we have and plant more for the future.

Broader implications for design

The principles of more-than-human design we used in Canberra also have broader applications[9]. Many environments around the world face similar challenges. By rethinking current approaches to design and planning, we can create more inclusive and resilient environments for many different lifeforms[10].

The essential change is to treat other species as innovators and expert participants in design. Extending existing efforts to communicate with whales[11], bats and honeybees[12], this approach uses AI to incorporate input from nonhuman lifeforms to produce new and better designs.

Our case study shows how participatory approaches that include nonhuman beings can work around human biases[13]. As a result, we unlock a far greater range of possible designs.

Fair design

The world faces many urgent environmental crises. We need innovative, inclusive design approaches to meet this challenge. Trees are already excellent designers, just as birds are excellent judges of their work – and if we include[14] their input we can create better “more-than-human” designs.

We believe that using AI to give a voice to non-human stakeholders can lead to better solutions in which many species can live together[15]. Our work in Canberra is an example of how participatory design can create more equitable and sustainable futures for all beings.

We acknowledge the initiative of Darren Le Roux[16] in researching and installing artificial habitat-structures to support biodiversity.

References

- ^ less than 5% remains (www.nespthreatenedspecies.edu.au)

- ^ large old trees (theconversation.com)

- ^ AI and machine learning (doi.org)

- ^ include non-human stakeholders (zenodo.org)

- ^ can provide (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ birds prefer small horizontal branches (doi.org)

- ^ bird interactions (theconversation.com)

- ^ continuous services (www.mdpi.com)

- ^ applications (pursuit.unimelb.edu.au)

- ^ many different lifeforms (animal-aided-design.de)

- ^ whales (www.wired.com)

- ^ bats and honeybees (www.scientificamerican.com)

- ^ human biases (www.nature.com)

- ^ include (zenodo.org)

- ^ many species can live together (dl.designresearchsociety.org)

- ^ Darren Le Roux (fennerschool.anu.edu.au)

Read more https://theconversation.com/what-makes-a-good-tree-we-used-ai-to-ask-birds-233281