Why the Voice referendum failed – and what the government hasn’t learned from it

- Written by Gabrielle Appleby, Professor of Law, UNSW Law School, UNSW Sydney

More than two years on, you’d be forgiven for thinking the story of the failure of the referendum on an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice has been neatly folded away and filed as a story of inevitable loss. Bipartisanship was essential. The country was not ready. Racism raised its ugly head. The proposal was too radical.

As we explore in our recently released book[1], contrary to some accounts, the Voice referendum was not doomed from the start. It was a carefully developed proposal for constitutional reform, crafted over more than a decade, supervised by successive federal governments from both sides of politics.

Its defeat was the product of a complex amalgam of factors. The Albanese government announced first and prepared later. It failed to genuinely engage with the First Nations people who had been developing this reform for years. It misread and was over-confident about the political terrain following the Coalition’s 2022 election defeat.

Then there was the No campaign, spearheaded by key opposition figures that openly relied on political lies and conspiracy claims[2], in a largely unregulated political and media environment.

But we explore an under-emphasised dimension of this story: the government’s own lack of preparation and respect for the reform it had committed to take to the people.

This article is an edited extract from our chapter in the new book The Failure of the Voice Referendum and the Future of Australian Democracy[3], edited by professors Gabrielle Appleby[4] and Megan Davis[5].

Announce first, prepare later

We are, unfortunately, seeing the lessons from the 2023 Voice referendum being identified by commentators in the government’s response to the Bondi attacks.

Political scientist professor Chris Wallace observed[6] what she refers to as “a now unmissable pattern in Anthony Albanese’s behaviour: overestimating his political judgement and being closed to alternative viewpoints and advice”.

The Voice referendum campaign required extensive preparation and the humility to listen and respond. Positive structural reform campaigns are hard. A successful campaign required groundwork: sustained civics education delivered to Australian voters, reform of referendum legislation and a holistic response to the challenges of misinformation.

Opposition to reform, on the other hand, is easy. You don’t have to present a coherent alternative proposal, something aptly demonstrated by the No campaign.

None of this groundwork was undertaken prior to the prime minister unilaterally sounding the starting gun for the referendum on election night in May 2022. No one involved in the proposal knew it would become part of the prime minister’s personal election-night pledge. The government’s subsequent attempts to prepare before the referendum were rushed and flawed.

From the moment the referendum was announced, the behaviour was set. Key decisions were made without meaningful consultation. The referendum’s timing, the wording of the constitutional amendment and the composition of advisory groups were all decided without the input of those who came up with the idea.

Outsourcing the politics

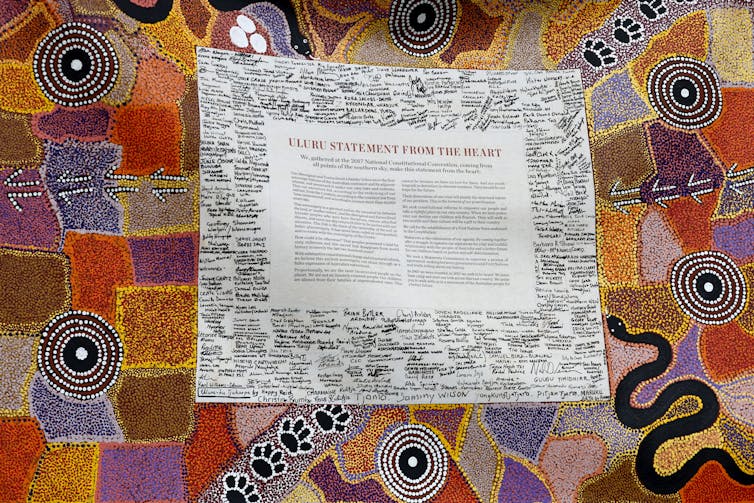

The government refused briefings from those involved in the proposal. This left ministers unprepared, unable to explain the genesis of the Uluru Statement from the Heart[7] and unable to articulate the purpose of the Voice.

At the same time, the government remained stubbornly uninterested in proposals from those who had been involved with the Voice process for 12 years. Reforming the machinery of referendums framework (including through the introduction of a fact-checking authority), releasing more details about the Voice’s design and engaging the Australian public through a citizen’s assembly were among the ignored suggestions.

As economist professor John Quiggin recently wrote[9], reflecting on the prime minister’s response to the Bondi terror attack, Albanese’s instinct is often to make the announcement and “leave the hard yards to others”.

That instinct was on full display during the Voice campaign. Political scientist Mark Kenny astutely observed a year after the referendum that the business (and weight) of politics and garnering bipartisanship was outsourced to First Nations people.

This matters because the Voice was never a symbolic flourish. It was not, as Albanese has since described it[10], a “gracious” and generous request from First Nations people seeking recognition.

The Voice was a serious and hardheaded reform that emerged from an unprecedented and deliberative process — the First Nations Regional Dialogues[11] and the Uluru Statement from the Heart[12].

The ongoing need

In May last year, Albanese’s government returned with a thumping majority. Some re-imagine the result as redemptive for the defeat of the Voice — or vindication of the result. This fundamentally misunderstands what was at stake.

Looking forward, the need for a Voice has not diminished. If anything, the years since the referendum has reinforced its necessity.

The government is back to cheering for economic empowerment[13]. It turns only to a minuscule group of well-funded Indigenous elites for consultation.

It also has a renewed focus on Closing the Gap. But this comes without addressing the structural reasons for why the gap persists, including the denial of First Nations input about the necessary solutions.

Read more: Progress on Closing the Gap is stagnant or going backwards. Here are 3 things to help fix it[14]

Some governments are trying to address these challenges at the state level. In 2025, after nearly a decade of negotiation, Victoria enacted legislation to give effect to Australia’s first statewide treaty[15].

Central to that agreement is a stable representative body, Gellung Warl. This makes permanent (or at least legislates) the First Peoples’ Assembly, empowered to speak to government and parliament on matters affecting Aboriginal people.

The logic mirrors the federal Voice because the need is the same. Without a durable representative institution first, Indigenous participation remains contingent, fragile and easily sidelined.

South Australia was the first state to have a First Nations Voice, and Victoria’s Treaty-as-Voice was next. Yet, they remain fragile reforms and limited to support from the Labor party in each state.

Australia is a federal system governed by a Constitution. We need constitutional guarantees[17] that insulate First Nations people from the vagaries of majoritarian politics.

At present, we appear far from any realistic proposal for constitutional reform on any issue, especially for First Nations. The prime minister has emphatically stated he will not take another proposal to referendum — not this term, and not at all.

But Australia’s democracy and constitutional institutions cannot afford stagnation. They require reconstruction and renewal to reflect the composition and challenges of contemporary society.

Preparing for the future

There will be another moment for structural constitutional change. When that inevitable moment is upon us, our hope is that Australia has developed the constitutional maturity that was lacking in 2023.

Research shows[18] the primary reason Australians voted “no” in 2023 is because they believed there was no mention of race in the Constitution. They ostensibly voted against putting it in.

But the Constitution is imbued with race and it has a races power[19]: a provision giving the Commonwealth the power to make special laws to govern people of a particular race. If Australians are to espouse pride in equality and fairness and the rule of law, constitutional history and civic education are fundamental to this.

Anthem Press[20] When inklings of constitutional change emerge, as they will, lessons from 2023 will be crucial. Sustained civics education[21] must become a permanent feature of our educational curriculum and democratic life, sooner rather than later. Regulatory reform is essential. Modernising referendum legislation (as repeatedly urged by parliamentary[22] inquiries[23]) can be done now, rather than during a campaign. So, too, can truth in political advertising laws[24]. One idea raised consistently is the creation of a standing constitutional commission. It would undertake research, consultation and develop future reform proposals. Constitutional change should not be so daunting. And then there is the hardest work of all: the work of a future proposal itself. Governments must approach structural reform not as a branding exercise or an act of political “courage”. It’s a process that improves Australian democracy and is worthy of sustained and earnest focus and commitment. It demands preparation, humility, openness and sustained engagement. This is the only way to have all Australians participating in change. References^ book (anthempress.com)^ conspiracy claims (www.theguardian.com)^ The Failure of the Voice Referendum and the Future of Australian Democracy (anthempress.com)^ Gabrielle Appleby (theconversation.com)^ Megan Davis (theconversation.com)^ observed (www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au)^ Uluru Statement from the Heart (theconversation.com)^ Con Chronis/AAP (photos.aap.com.au)^ wrote (johnquigginblog.substack.com)^ described it (www.afr.com)^ Regional Dialogues (ulurustatement.org)^ Uluru Statement from the Heart (ulurustatement.org)^ economic empowerment (www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au)^ Progress on Closing the Gap is stagnant or going backwards. Here are 3 things to help fix it (theconversation.com)^ first statewide treaty (theconversation.com)^ Justin McManus/AAP (photos.aap.com.au)^ need constitutional guarantees (www.firstpeopleslaw.com)^ Research shows (polis.cass.anu.edu.au)^ races power (www.austlii.edu.au)^ Anthem Press (anthempress.com)^ Sustained civics education (theconversation.com)^ parliamentary (www.aph.gov.au)^ inquiries (theconversation.com)^ truth in political advertising laws (theconversation.com)

Anthem Press[20] When inklings of constitutional change emerge, as they will, lessons from 2023 will be crucial. Sustained civics education[21] must become a permanent feature of our educational curriculum and democratic life, sooner rather than later. Regulatory reform is essential. Modernising referendum legislation (as repeatedly urged by parliamentary[22] inquiries[23]) can be done now, rather than during a campaign. So, too, can truth in political advertising laws[24]. One idea raised consistently is the creation of a standing constitutional commission. It would undertake research, consultation and develop future reform proposals. Constitutional change should not be so daunting. And then there is the hardest work of all: the work of a future proposal itself. Governments must approach structural reform not as a branding exercise or an act of political “courage”. It’s a process that improves Australian democracy and is worthy of sustained and earnest focus and commitment. It demands preparation, humility, openness and sustained engagement. This is the only way to have all Australians participating in change. References^ book (anthempress.com)^ conspiracy claims (www.theguardian.com)^ The Failure of the Voice Referendum and the Future of Australian Democracy (anthempress.com)^ Gabrielle Appleby (theconversation.com)^ Megan Davis (theconversation.com)^ observed (www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au)^ Uluru Statement from the Heart (theconversation.com)^ Con Chronis/AAP (photos.aap.com.au)^ wrote (johnquigginblog.substack.com)^ described it (www.afr.com)^ Regional Dialogues (ulurustatement.org)^ Uluru Statement from the Heart (ulurustatement.org)^ economic empowerment (www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au)^ Progress on Closing the Gap is stagnant or going backwards. Here are 3 things to help fix it (theconversation.com)^ first statewide treaty (theconversation.com)^ Justin McManus/AAP (photos.aap.com.au)^ need constitutional guarantees (www.firstpeopleslaw.com)^ Research shows (polis.cass.anu.edu.au)^ races power (www.austlii.edu.au)^ Anthem Press (anthempress.com)^ Sustained civics education (theconversation.com)^ parliamentary (www.aph.gov.au)^ inquiries (theconversation.com)^ truth in political advertising laws (theconversation.com)