why our next visit to the giant planets will be so important (and just as difficult)

- Written by Chris James, ARC DECRA Fellow, Centre for Hypersonics, School of Mechanical and Mining Engineering, The University of Queensland

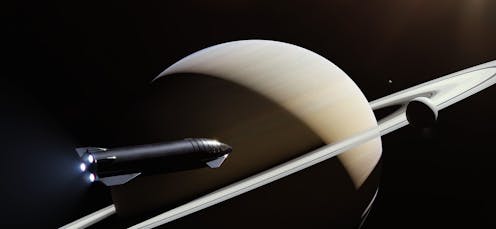

The giant planets – Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune - are some of the most awe-inspiring in our Solar System, and have great importance for space research and our comprehension of the greater universe.

Yet they remain the least explored – especially the “ice giants” Uranus and Neptune – due to their distance from Earth, and the extreme conditions spacecraft must survive to enter their atmospheres. As such, they’re also the least understood planets in the Solar System.

Our ongoing[1] research[2] looks at how to overcome the harsh entry conditions experienced during giant planet missions. As we look forward to potential future missions, here’s what we might expect.

But first, what are giant planets?

Unlike rocky planets, giant planets don’t have a surface to land on. Even in their lower atmospheres they remain gaseous, reaching extremely high pressures that would crush any spacecraft well before it could land on anything solid.

There are two types of giant planets: gas giants and ice giants.

The larger Jupiter and Saturn are gas giants. These are mainly made of hydrogen and helium, with an outer gaseous layer and a partially liquid “metallic” layer below that. They’re also believed to have a small rocky core.

Uranus and Neptune have similar outer atmospheres and rocky cores, but their inner layer is made up of about 65% water and other so-called “ices” (although these technically remain liquid) such as methane and ammonia[3].

Slingshots to the edge of the Solar System

Any giant planet mission is extremely difficult. Still, there have been some past missions sent to the gas giants.

NASA’s 1989 Galileo mission had to slingshot around Venus and Earth to give it enough momentum to get to Jupiter[4], which it orbited for eight years. The 2011 Juno mission[5] spent five years in transit, using a flyby around Earth to reach Jupiter (which it still orbits).

Similarly, the Cassini-Huygens mission run by NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) took seven years[6] to reach Saturn. The spacecraft spent 13 years exploring the planet and its surrounds, and launched a probe to explore Saturn’s moon, Titan[7].

Flight times get even longer for the two ice giants, which are much further from the Sun. Neither has had a dedicated mission so far.

A complex journey

The last and only spacecraft to visit the ice giants was Voyager 2[8], which flew by Uranus in 1986 and Neptune in 1989.

While momentum is building for a return, it won’t be simple. If we launch during the next convenient launch windows[9] of 2030–34 for Uranus and 2029–30 for Neptune, flight times would vary from 11 to 15 years.

A major issue is power. The Juno spacecraft is the most distant object from the Sun to have used solar panels[10]. It orbits Jupiter, which is five times further away[11] from the Sun than Earth is. Yet, where Juno’s solar cells would generate 14 kilowatts of continuous power on Earth, they only generate 0.5kW at Jupiter[12].

Meanwhile, Uranus and Neptune are 20 and 30 times further away, respectively, from the Sun than Earth is. Power for these missions would have to be generated from the radioactive decay of plutonium[13] (the power source for both the Galileo and Cassini missions).

This radioactive decay can damage and interfere with instruments. It is therefore reserved for spacecraft which really need it, such as missions operating far away from the Sun.

Read more: So a helicopter flew on Mars for the first time. A space physicist explains why that's such a big deal[14]

Fighting the heat

The massive scale of giant planets means orbit speeds for incoming spacecraft are incredibly fast. And these speeds greatly heat up the spacecraft.

The Galileo probe entered Jupiter’s atmosphere at 47.5 kilometres per second[15], surviving the harshest entry conditions ever experienced by an entry probe. The shock layer which formed at the front of the spacecraft during entry reached a temperature of 16,000℃ – around three times the temperature of the Sun’s surface.

Even so, the distribution of the heat shield’s[16] mass was found to be inefficient – showing we still have a lot to learn about entering giant planets.

Proposed future probe missions to Uranus and Neptune would occur at slower entry speeds of 22km/s and 26km/s[17], respectively.

For this, NASA have developed a tough but relatively lightweight material woven from carbon fibre, called HEEET[18] (Heatshield for Extreme Entry Environment Technology), designed specifically for surviving giant planet and Venusian entry.

While the material has been tested with a full-scale prototype[19], it has yet to fly on a mission.

The next steps

In 2024, NASA’s Europa Clipper mission will launch[20] to investigate Jupiter’s moon Europa, which is believed to house an ocean of liquid water[21] below its icy surface, where signs of life may be found. The Dragonfly[22] mission, planned to launch in 2026, will similarly aim to search for signs of life on Saturn’s moon Titan.

There are plans for a joint NASA-ESA mission[23] to visit one of the ice giants within the upcoming launch window. But while there has been extensive[24] preparation[25], it’s undecided which ice giant will be visited.

A single mission to both planets is being considered. An entry probe is planned, too. But if the mission visits both planets, it’s undecided which planet’s atmosphere the probe would explore[26].

If we want to meet the upcoming launch window, it’s expected mission concepts will need to be finalised by 2025[27], at the latest. In other words, crunch time is coming.

Should a mission go forward, the two most important goals[28] for NASA’s scientists will be to determine the interior makeup of ice giants (exactly what they are made of) and their composition (how they are formed).

Other objectives will include studying their magnetic fields, which are very different[29] to gas giants and all other types of planets.

They’ll also want to study the heat released by both Uranus and Neptune, which both have average temperatures of around -200℃. All giant planets are meant to be very slowly cooling down, as they release energy gained during their formation.

This heat release can be detected for Jupiter, Saturn and Neptune. Uranus, however, doesn’t seem to release heat – and scientists don’t know why.

References

- ^ ongoing (arc.aiaa.org)

- ^ research (doi.org)

- ^ methane and ammonia (www.lpi.usra.edu)

- ^ get to Jupiter (www.nasa.gov)

- ^ Juno mission (spaceflight101.com)

- ^ took seven years (sci.esa.int)

- ^ Titan (solarsystem.nasa.gov)

- ^ Voyager 2 (solarsystem.nasa.gov)

- ^ launch windows (www.lpi.usra.edu)

- ^ used solar panels (www.jpl.nasa.gov)

- ^ five times further away (solarsystem.nasa.gov)

- ^ generate 0.5kW at Jupiter (www.jpl.nasa.gov)

- ^ decay of plutonium (solarsystem.nasa.gov)

- ^ So a helicopter flew on Mars for the first time. A space physicist explains why that's such a big deal (theconversation.com)

- ^ 47.5 kilometres per second (solarsystem.nasa.gov)

- ^ heat shield’s (arc.aiaa.org)

- ^ 22km/s and 26km/s (link.springer.com)

- ^ HEEET (www.nasa.gov)

- ^ full-scale prototype (www.nasa.gov)

- ^ will launch (europa.nasa.gov)

- ^ ocean of liquid water (europa.nasa.gov)

- ^ Dragonfly (www.nasa.gov)

- ^ NASA-ESA mission (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ extensive (www.lpi.usra.edu)

- ^ preparation (sci.esa.int)

- ^ atmosphere the probe would explore (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ by 2025 (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ goals (www.lpi.usra.edu)

- ^ very different (www.lpi.usra.edu)