the master of shimmering luminosity, who painted difficult paintings and yet made them lucid and accessible

- Written by Sasha Grishin, Adjunct Professor of Art History, Australian National University

Pierre Bonnard, unlike his older contemporary, Paul Gauguin[1], never visited Australia, yet Bonnard’s influence on Australian art is pervasive and profound.

This unusual and magnificent exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria allows us to see Bonnard like never before.

In part, this is due to the exceptional depth in the selection of the more than 100 works by Bonnard for this exhibition, largely drawn on the extensive collection held by Paris’s Musée d’Orsay.

Also, in part, by a stroke of genius in commissioning the celebrated Paris-based architect and designer India Mahdavi to create the exhibition’s scenography.

The exhibition is like a creative collaboration between the artist and the designer. Architectural props, painted walls, special carpets and furnishings all combine to create an intimate environment, setting the mood to be captivated by the magic of Bonnard’s colour.

A solitary path

Like his contemporary, the Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky[2], Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947) initially studied law. After graduating, he abandoned it to pursue a career as an artist.

Also like Kandinsky, he lived and worked in the centre of the art world of his day. He was associated with many of the key artists, and yet, in the final analysis, Bonnard – like Kandinsky – was essentially a loner who traced for himself a solitary path.

In the final decade of the 19th century, Bonnard together with several other young Paris-based artists, including Edouard Vuillard[3], Maurice Denis[4] and the sculptor Aristide Maillol[5], formed an artistic brotherhood on similar lines to that of the Nazarenes[6] and the Pre-Raphaelites[7].

They called themselves “The Nabis[8]” (a Hebrew and Arabic word meaning “prophets”) and essentially adopted Gauguin’s aesthetic stance of Synthetism[9].

Read more: How computer science was used to reveal Gauguin’s printmaking techniques[10]

The basic argument of Synthetism was that the art object an artist produced was a synthesis of the artist’s own vision, training, the medium involved, as well as the stimulus of the scene or object depicted.

In other words, it was a theory which gave the creative person greater artistic licence in interpreting a scene or composition in a work of art, rather than merely transcribing it.

Early Bonnard Nabis masterworks include Twilight, or The croquet game (1892), and Paris, Rue de Parme on Bastille Day (1890). These revel in the qualities of the flattened picture plane, the unexpected viewpoints and the strong ornamental properties.

Siesta (1900), a great painting from the NGV’s own collection, has Bonnard moving towards a lighter and more luminous palette with adventurous spatial constructions.

Ostensibly, it is simply a painting of the model shown within the intimate space of the artist’s studio.

However, as you enter the picture space, you realise the figure is being presented from a high angle. You literally peer into the space where the mass of crumpled sheets and soft sensuous flesh meet the richly patterned wallpaper and carpet that seem to envelop and surround them.

Although the figure in her pose may allude to a well-known statue from classical antiquity, the rendition is thoroughly modern. The bedside table thrusts diagonally towards the figure and opens the work to a whole host of Freudian interpretations.

While Bonnard here may well be drawing on artistic sources as diverse as Manet, Matisse and Cézanne, the painting itself is a wonderfully resolved and unified artistic statement – a triumph of visual intelligence.

It is displayed together with the photographs Bonnard took of his model that may have served as source material for the artist.

Bonnard was inspired by photography and the unexpected angles and the cropping of images and implemented these strategies in his art.

The window

The window (1925) is a beautiful and lyrical painting executed by Bonnard while staying with a woman called Marthe in a rented holiday villa at Le Cannet, near Cannes, in the south of France.

Looking out of the window, we see the red roofs of the little town of Le Cannet and beyond that sweeping Cézannesque hills.

Although his chief preoccupation appears to have been with the attempt to balance the tonal values of his palette and to create the compositional structure through colour, the artist also seems intent on loading the work with a private iconography.

In the foreground on the table lies a book and a sheet of paper with writing implements. On the balcony, in a central position, appears the head of Marthe, shown in profile reading.

The book is clearly identified by an inscription on its cover as the novel Marie[11] by Peter Nansen that Bonnard illustrated.

If one adds together the visual clues, one possible interpretation is Marie was Marthe’s real name and in the year the painting was painted, 1925, Bonnard finally married Marthe. One could speculate that the piece of paper alludes to a marriage certificate.

Read more: Who was Marthe Bonnard? New evidence paints a different picture of Pierre Bonnard’s wife and model[12]

The master of shimmering luminosity

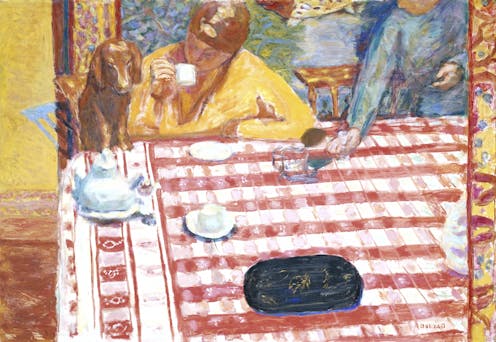

Ultimately, Bonnard was the master of shimmering luminosity who painted very clever and difficult paintings and yet made them appear lucid and accessible. The open window, the doorway and particularly a mirror were his favourite ploys to give space an ambiguous but convincing formal structure.

His painted surfaces have a textural presence with choppy, visible brushstrokes.

Unlike the Impressionists who followed the reliable path of contrasting complementary colours to make them visually vibrate, Bonnard would set himself impossible tasks such as juxtaposing pink and orange or lemon yellow and olive green.

He then would cast his central figures against the light and would work on a solution until each tone appears alive, shimmering and vibrating.

In the context of Australian art, scores of artists responded to his work – Emanuel Phillips Fox[13], Ethel Carrick[14], John Brack[15], Fred Williams[16], Jon Molvig[17], Brett Whiteley[18] and William Robinson[19] among them.

While I have viewed many Bonnard exhibitions in Australia and abroad, this is the most moving and subtle display that I have encountered. I left the show spiritually refreshed and with tears in my eyes.

Pierre Bonnard: Designed by India Mahdavi is at the National Gallery of Victoria International until October 8.

Read more: Pierre Bonnard at the Tate: the surprising reasons we love art[20]

References

- ^ Paul Gauguin (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ Wassily Kandinsky (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ Edouard Vuillard (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ Maurice Denis (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ Aristide Maillol (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ Nazarenes (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ Pre-Raphaelites (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ The Nabis (www.tate.org.uk)

- ^ Synthetism (www.tate.org.uk)

- ^ How computer science was used to reveal Gauguin’s printmaking techniques (theconversation.com)

- ^ Marie (www.metmuseum.org)

- ^ Who was Marthe Bonnard? New evidence paints a different picture of Pierre Bonnard’s wife and model (theconversation.com)

- ^ Emanuel Phillips Fox (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ Ethel Carrick (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ John Brack (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ Fred Williams (theconversation.com)

- ^ Jon Molvig (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ Brett Whiteley (theconversation.com)

- ^ William Robinson (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ Pierre Bonnard at the Tate: the surprising reasons we love art (theconversation.com)